The sands bear telltale signs of our quarry having moved across it quite recently.

The sands bear telltale signs of our quarry having moved across it quite recently.

But, the wind has already begun shifting grains of sand onto the tracks, so we hurry on to try and find the animal before we lose the trail completely.

Panting, we reach a little scrubby bush and look carefully all around it. No sign of anything!

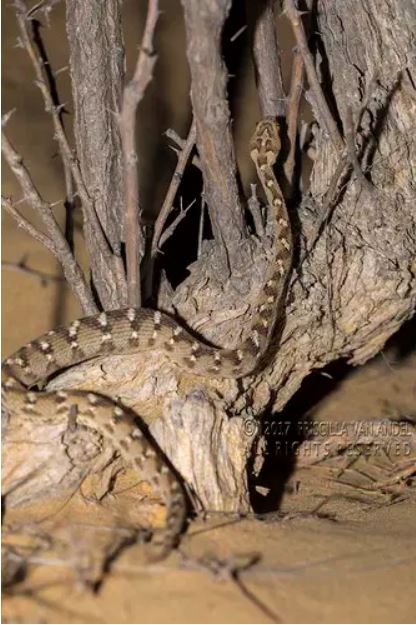

Then, when we get down on our knees and carefully peer beneath the foliage, we see the typical patterning on one coil of the saw-scaled viper.

The reason this particular one was special after seeing hundreds of saw-scaled viper throughout my life, was that this snake was in Rajasthan and a different subspecies from the one I was used to.

Saw-scaled vipers in South India belong to the subspecies Echis carinatus carinatus and grow to a maximum length of about 40 cm.

The ones in Rajasthan are Sochurek’s saw-scaled viper (Echis carinatus sochureki) and grow to twice that length.

Aside from the disparity in size, Sochurek’s saw-scaled vipers have a very different pattern from their southern cousins.

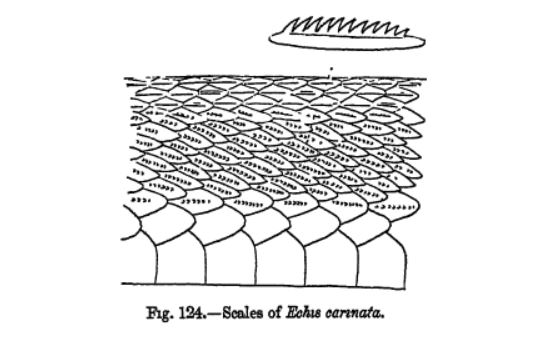

These enigmatic vipers get their name from rows of strongly keeled scales along their sides, which are oriented upward as opposed to backward, which is the norm in most snakes.

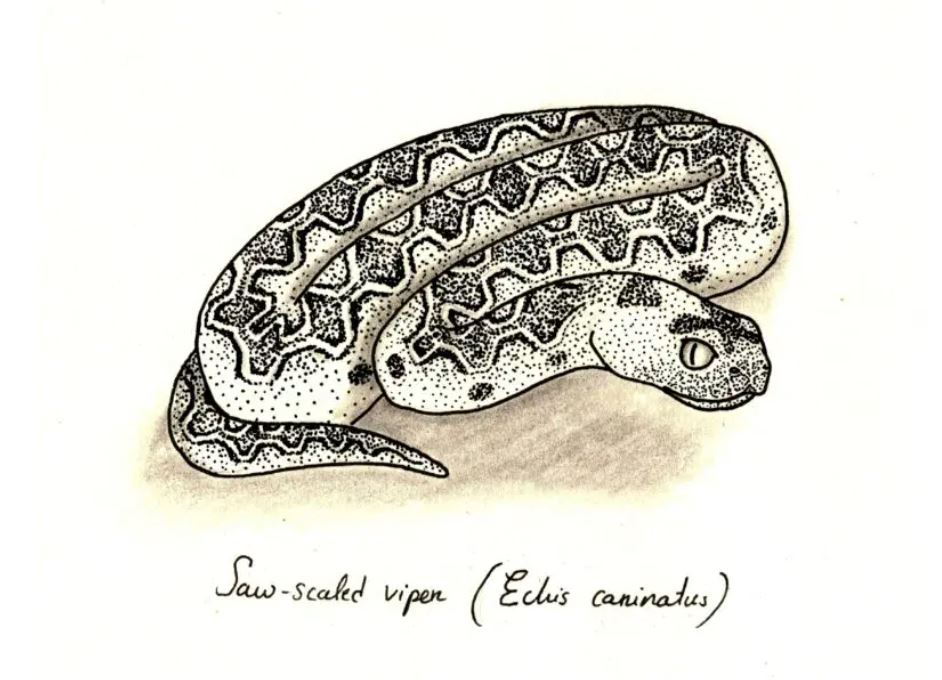

When threatened, the saw-scaled viper bunches its body into a tight ‘S’ shape, and moves to rub these scales together, creating a raspy sound, much like a tiny saw.

It’s truly a spectacle to watch these little snakes create such a significant sound with their scales. The process by which animals rub body parts together to make sounds is called stridulation.

It’s what enables us to identify the unique tracks they leave behind

The group of snakes called saw-scaled vipers includes twelve species currently. India has one species with the two subspecies.

Having said that, it is quite likely that further taxonomic work will split this into more species within the country.

This group of snakes is believed to be involved in the most number of snakebite cases in the world, and in Africa they are believed to cause the highest number of deaths.

In India, they don’t cause мคหy fatalities, but, their bites can cause a lot of tissue damage and permanent loss of limb if not treated well and promptly.

heir cryptic lifestyle and inclination to hide rather than flee makes them particularly dangerous.

Saw-scaled vipers can hide under a single leaf or in the shortest of ground cover. People walking barefoot are particularly at risk of stepping on one and getting bitten.

Their venom is primarily haemotoxic and cytotoxic, which prevents blood from clotting and causes significant cell and tissue damage.

In India, we have polyvalent antivenom that also works on the venom of this species.

Very little work has been done on the venom of this species and ongoing research is showing significant variation of venom within the species.

One reason for the variation of venom could be the difference in diet that this species has across its range as well as through its lifespan.

In South India, saw-scaled vipers are known to consume insects, small reptiles, and other invertebrates.

The ones in Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Rajasthan have been documented even feeding on scorpions. They’re also known to eat the young of small rodents and shrews.

Young saw-scaled vipers probably feed exclusively on small insects and other invertebrates. As they grow larger, they probably include some amphibians and reptiles into their diet.

Consequently, there’s a very good chance that the venoms of young saw-scaled vipers could be different from their adult counterparts. However, no research has been done on these aspects.

Interestingly, even though all saw-scaled vipers belong to one genus, Echis, some of them give birth to live young while other species lay eggs.

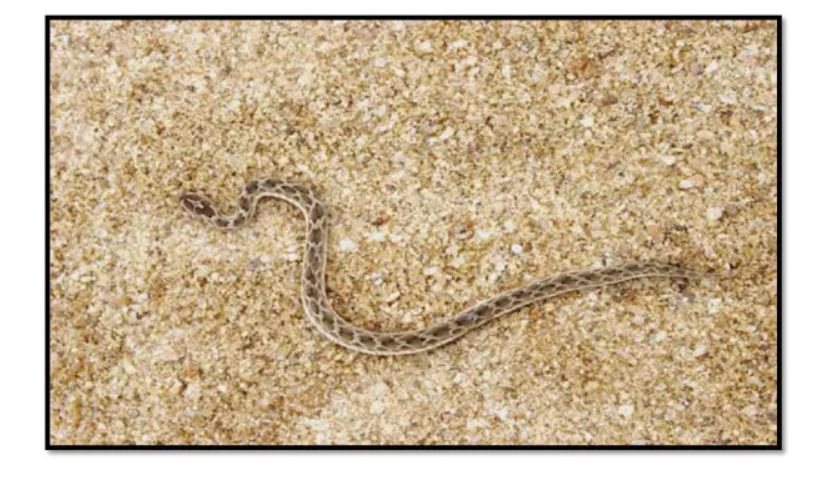

Both the known subspecies in India give birth to live young. Our tiny South Indian saw-scaled vipers are born no bigger than an average earthworm.

They shed their skin for the first т¡мe within a day or so, and are on their own from the beginning. Even the young of much larger snakes are in constant danger of getting eaten.

These little noodles are fair game for anything from birds, frogs, mammals, lizards, and even some scorpions and spiders!

Their clutch sizes aren’t known to be particularly large. Ten neonates would be a